Museums, the Shutdown and Ambreen Butt at NMWA

By • January 22, 2019 0 1047

At the time I am writing this, the shutdown is entering its 28th day.

While it is implausible that the temporary closure of federally funded art museums does any observable or lasting damage to the fabric of our country, it’s a complicated premise.

Art exists in an interstitial space, apart from the established, conservative orders of government and economics. As a result, there’s a tension in our culture between capitalist and creative forces.

Capitalism depends on entrepreneurial creativity to continually generate new ideas. This allows it to keep pace with the changing environment of culture itself. And art is one of the major conduits of cultural development. Artists are cultural entrepreneurs, and artistic endeavors are in some sense at the base of everything.

This is problematic for our conservative political culture, which promotes capitalist social structures but is not temperamentally inclined to appreciate art. So, while our government tries to foster entrepreneurship, it often devalues creative activity.

But art can offer things that political and economic machines fundamentally can’t. For one, art quite literally teaches us how to look at things in new and different ways. Art can present valuable critiques of the established order. It can offer alternative visions of power, virtue and history, of what it means to cultivate and sustain life. Art provides a different, typically deeper and less rigid set of values than commercial realpolitik, especially amid a political climate as suffocating as today’s.

Maybe the federal closure of the Smithsonian museums and the National Gallery of Art is no more than a poetic footnote in this ideological warfare that is largely the reason for the shutdown to begin with. But with so many of our museum doors shuttered, we are confronted with the bleak reality of what our cities would look like without their cultural endeavors.

Our museums are the stewards of cultural history, achievement and development. At their best, they help us look into our past while providing ideas for the future.

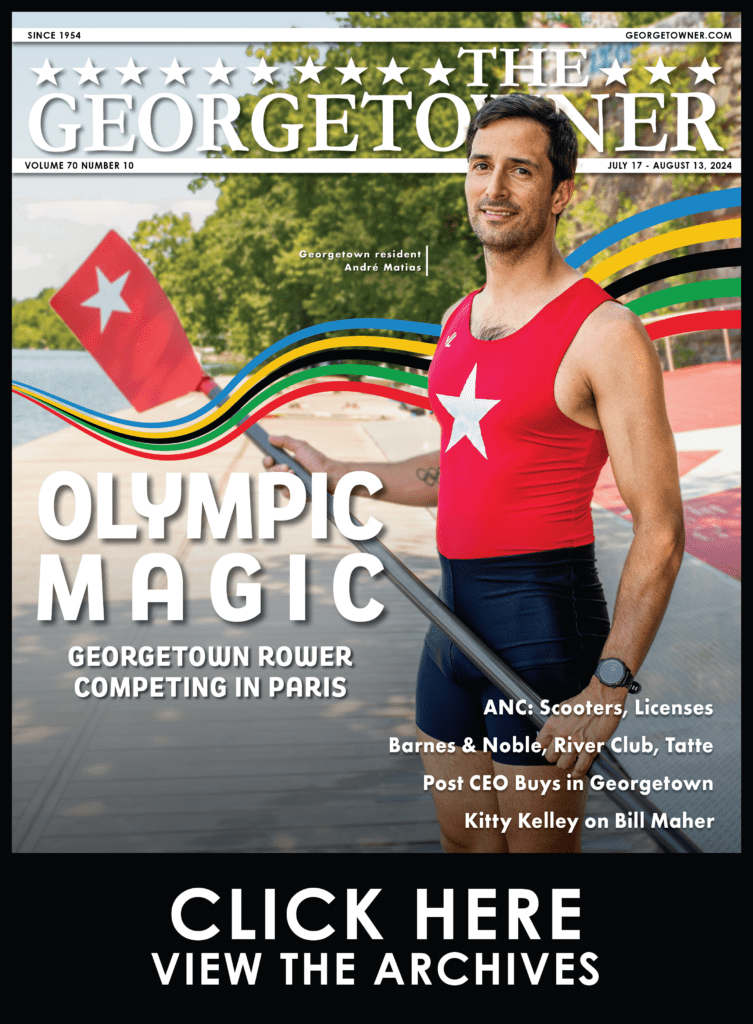

Ambreen Butt’s work did this for me. At the National Museum of Women in the Arts, one of our city’s private art museums that thankfully remain open, “Ambreen Butt: Mark My Words,” on view through April 14, is an exhibition of startling relevance for this moment.

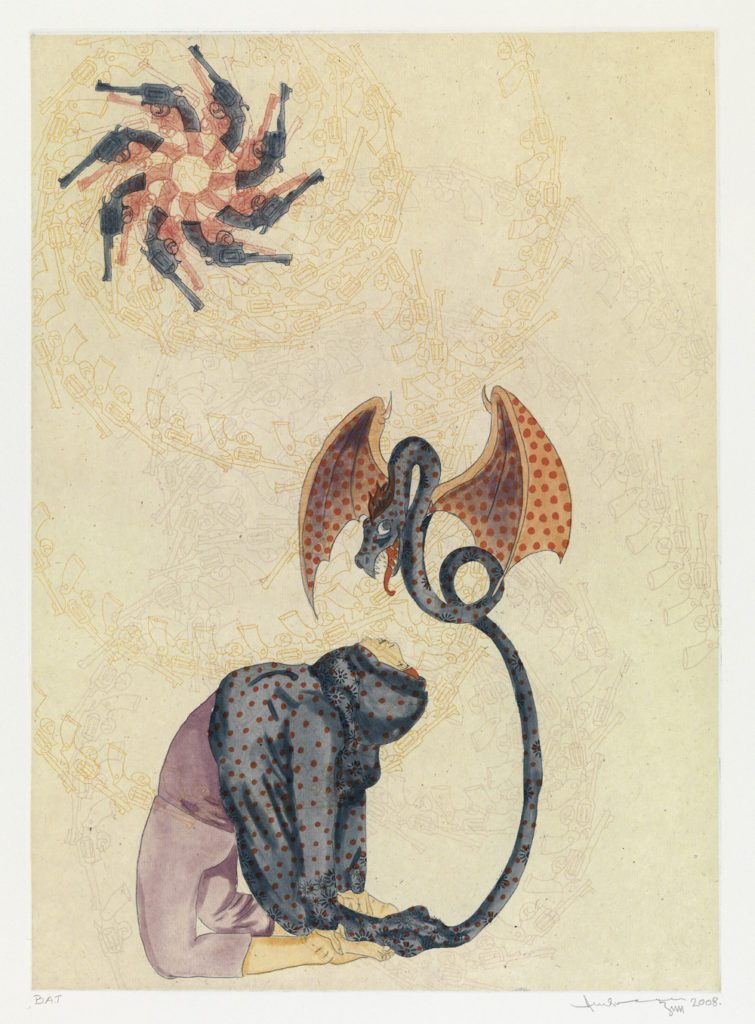

Born in 1969, Butt grapples in her work with freedom of expression and the role of art as social commentary. Her works on paper combine her training in traditional Persian and Indian miniature painting with conceptual and political art that she encountered after relocating from Pakistan to the United States in 1993.

Blending an astonishing variety of techniques, from etching and drypoint to painting, threading, collage, gilding and staining, Butt’s exquisite handwork and fine detail draw you in at a glance with their intriguing beauty to reveal complex layers of meaning.

It can feel a bit out of touch to discuss the aesthetic appeal of artwork with such deep political charge. Butt’s works tackle subjects like child victims of drone-bombing, female student protests in Pakistan and First Amendment rights clashing with national security concerns.

However, art with a political message must succeed as art before it can be considered for its content. From Picasso’s “Guernica” to Shirin Neshat’s riveting photographs inscribed with Farsi poetry, the most indelible politically charged artwork is undeniably beautiful. Butt is clearly aware of this, and her works succeed in their pursuit of beauty.

Her “Say My Name” series is dedicated to forgotten youth casualties of American drone strikes in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Each work displays a mosaic of tiny paper shreds in mesmerizing patterns, each scrap repeating the name of a single victim. The allure of these undulating, luminescent patterns against the tea-stained paper converges disturbingly with the ugly reality of the violence to which they speak.

Another series, “Daughters of the East,” was created in response to female student protestors who stood against the military siege of the Red Mosque in Islamabad. Here, Butt forgoes the classical structure of her otherwise traditional forms and techniques. While the individual works lose some of their aesthetic force, they overstate their political message in a way that is brutally, effectively unapologetic.

The etchings are individually beautiful, sensitive and delicate, yet powerful, complicated, often troubling in a way that makes sense with the image — a veiled metaphor for the perception versus reality of women.

In “Untitled (Silver Woman),” a woman stands at the center of the composition, dissolving into a cloud of flower petals and ladybugs. Her face is visible but obscured. She is both specific and anonymous, one woman and all women, recalling Indic and Buddhist philosophies, in which the one and the infinite exist simultaneously.

This motif of dissolving appears throughout the exhibition. A tiger unravels into a flickering of its stripes. Mosquitoes, butterflies and ladybugs overwhelm a composition’s subject. Fish dissolve into geometric patterns. Even human figures fade into obscurity through the layering of translucent paper.

Perhaps the notion of that which dissolves is a fitting note on which to end. I hope that by The Georgetowner’s next issue, this unfortunate episode of government dysfunction has dissolved into the past and our national museums have reopened along with the rest of our federal agencies. Meanwhile, let’s give our attention and support to the museums and galleries in our city that remain open.