Appreciating D.C.’s Jazz History

By • April 10, 2019 0 1822

You might think for now that April is cherry blossom month, or it’s a month for April showers or the month that a poet or poets called the cruelest of the year.

April is all of that, but April is also Jazz Appreciation Month, aka JAM, by way of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, which created the designation in 2001 to “recognize and celebrate the extraordinary heritage and history of jazz.”

The focus of this year’s JAM is “Jazz Beyond Borders,” which not only looks at the “dynamic ways jazz can unite people across the culture and geography” but also highlights the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra’s upcoming tour, hitting cities in North America, Europe and Asia.

Nat King Cole, the smooth-voiced, “Unforgettable” singer of jazz ballads and vocal classics (and father of the late Natalie Cole) is this year’s JAM featured artist.

Jazz is many things to almost everyone. Phrases abound: jazz is love, jazz is freedom, jazz flies, jazz is original. It’s been called America’s classical music. Jazz in its history carries irony, dichotomy, aspiration, the weight and sometimes burdens of its roots. It spirals out of a wellspring of blues, gospel, rock and rockabilly. It is a trifecta of cool — as a style, as a sound and as a way of being. It’s unfettered and, at the same time, as disciplined as math; precise, yet in flight.

It has a history of dramatic personas and personalities — performers, musicians, composers and singers who left indelible impressions by the way they sang, played, explored — to the point of achieving the status of legend or of royalty: the Duke, the Count, Lady Day and so on, as in Ellington, Basie and Billie Holiday.

Jazz is also our city’s music. Duke Ellington lived and played here, great singers sang here in churches, in clubs and at the Lincoln and Howard Theatres. If there was a Harlem Renaissance, there was one here, too. It remains in places like Blues Alley and Twins, in the resurrected Lincoln and Howard. And it had its homegrown legends like Shirley Horn and Buck Hill, who died only a couple of years ago at 90.

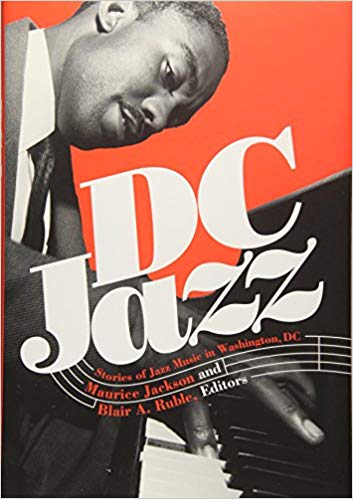

The spirit of jazz and jazz history will be found on Wednesday, April 17, at Mt. Zion United Methodist Church, at 1334 29th St. in Georgetown, when the Citizens Association of Georgetown hosts Georgetown University’s Maurice Jackson, co-editor of “DC Jazz: Stories of Jazz Music in Washington, DC,” conversing with local jazz greats Blair Ruble, Bridget Arnwine and Rusty Hassan. A reception at 6:30 p.m. precedes the program, from 7 to 8 p.m.

It’s an appropriate location for such an event. Mt. Zion was one of the keystones of a once thriving and culturally and musically rich African American community.

The book is a treasure trove of history, deeply researched and often tightly annotated. It’s something of a landmark history, where all sorts of personalities, peoples, places and things pop up, sometimes feeling like a print version of a riff by a jazz trio or a quartet, going from here to there, picked up by some other player in another way, always returning home.

The arrangement of the book is like an arrangement of a composition or, as Jason Moran, artistic director for jazz at the Kennedy Center, writes in a foreword: “Jazz has always been about community because of a revolutionary idea: the song is shared by every member of the band.”

Ellington figures strongly in the book, along with tales of origins, the building of communities and identity and all the legendary players that made D.C. a kind of jazz city, always evolving. It’s full of contributions from people steeped in jazz, including Willard Jenkins, current artistic director of the DC Jazz Festival, poet E. Ethelbert Miller and producer Bill Brower, along with Ruble and Jackson, who serve as co-editors of the book. Jackson teaches history and African American studies at Georgetown and Ruble is the author of “Washington’s U Street: A Biography.”

Jazz is at heart a personal experience, touched by life experience, which seems a birthright for some, a gratifying accident for others. As a kid and a German immigrant, growing up in small-town America, I had no experience of jazz until, stationed in New York in 1961 as part of my army service, on leave in Manhattan, I stumbled into a place called the Metropole and encountered Lionel Hampton. I had never seen anybody play the vibes, or heard the music being made, but it created vistas in a small, smoke-filled bar and enlarged the world for me.

I was fortunate: a phone interview with Basie, who at a concert in Oakland announced “Ladies and gentlemen, the Duke is dead”; seeing Dizzy walk along M Street in Georgetown on his way for morning coffee before heading to Blues Alley; listening to Nina Simone sing “Ain’t Got No” in a stadium on a hot summer day (wearing a white mink); watching two bass players, a youngster and an oldster, dueling; chancing to hear Ella sing scat at Wolf Trap; arguing with my neighbor in Lanier Heights, who remembered the glory days of U Street, about the best singer to sing “My Funny Valentine” (Chaka Khan was his choice).

You can add this: Miller, the poet, writing about Ellington:

what did Ellington mean

when he said

”I love you madly”

his hands touching a

piano not made of flesh

Probably everything. One woman says: jazz is love, after all.