Marcel Duchamp at the Hirshhorn

By • January 14, 2020 0 1882

Few people truly altered the course of history. Genghis Kahn, Isaac Newton, Karl Marx, Albert Einstein. Fewer still are artists. Da Vinci. Walter Gropius, maybe.

Among 20th-century artists, Picasso, Pollock and Warhol are probably the names that would bubble most immediately to the surface of this hypothetical listicle. However, I’d like to submit Marcel Duchamp for primary consideration.

At the Hirshhorn through Oct. 15, “Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection,” explores Duchamp’s monumental influence through and past the scope of his era.

Our cultural landscape would look radically different today had Duchamp never set foot in it. Had he been properly understood from the beginning of his complicated, labyrinthine career, that alone may have carved out everything between Cubism and Post-Modernism.

I’m not saying this would have been a good thing. Lots of tremendous, moving, important and beautiful work happened in that intervening time. I might even argue that modern art would have been far more beautiful had Duchamp not been involved. The idea of a work, he stated, takes primacy over craftsmanship or aesthetics. It is the foundation of conceptual art and perhaps the most influential idea in 20th-century art.

In 1907, Picasso painted “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” which — inasmuch as this can be attributed to a single work — was the spark that blasted Western painting irreversibly toward abstraction.

Five years later, in 1912, Duchamp painted “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.” A blend of Cubism and Futurism, the painting was ridiculously criticized for its misrepresentation of Cubism, at a time when Cubism itself was being lauded for its disregard of figural painting traditions.

The very next year, Duchamp made his first readymade, “Bicycle Wheel,” a bicycle fork with the front wheel mounted upside down on a wooden stool. While he claimed to have originally made it as a kind of meditative distraction, it became, in effect, the first piece of conceptual art. Four years after that, in 1917, when Picasso was at the height of his influence, Duchamp pushed his concept to an infamous extreme with “Fountain,” a common men’s urinal, which he signed R. Mutt and displayed in a gallery.

The vast majority of the art world did not catch up to him for 30 years.

It was not for another generation that Andy Warhol began appropriating “readymade” and “found” material in his work through popular iconography and media images. Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg employed found symbols and objects — as well as colors, letters and numbers — and divorced them from their intended meaning. Mel Bochner dealt in pure theory, often writing out his art concepts to stand in for the finished works, while Donald Judd and Robert Irwin manipulated space, shape and light to create purely sensorial experiences.

The notion of conceptual art can be an enormous pill. It abjures aesthetics, dismisses craftsmanship and embraces the mechanical over the handmade. It’s a paradoxical challenge to fine art enthusiasts, who are typically aesthetes. It also sets up the general public as a foil to the artwork. The works are concepts, not tangible assets for the purpose of aesthetic scrutiny. So what are we meant to look at?

In many ways this was Duchamp’s point: that art is ultimately no more than just so much prescribed meaning. But what this often looks like is a lot of confused museumgoers staring at a urinal or a wooden plank leaning on a wall and feeling annoyed and a little embarrassed — although it doesn’t seem like Duchamp harbored particular contempt for the artgoing public or ever intended to shame them.

There is no doubt that Duchamp should be recognized for his contributions to art and philosophy. But I suppose what I’ve been working toward here is a simple question: How are we supposed to experience this show?

Duchamp didn’t make art that acted like art. He made art that acted like thoughts. They are conceptual puzzles in perpetual states of reorganization.

Furthermore, while there are certainly noteworthy objects and drawings in the exhibition, the works on view seem more like a library collection of Duchamp’s papers and second-edition materials.

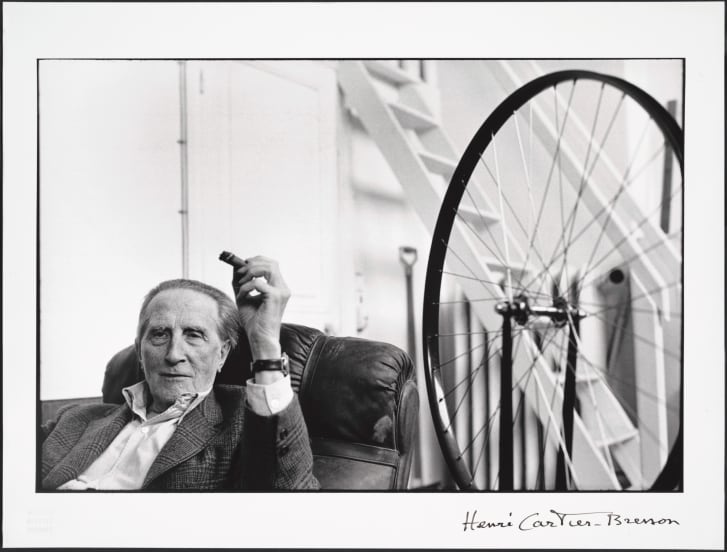

Photographic portraits do a lot of work to illuminate the idea of Duchamp as an enigma incarnate. A photo by Victor Obsatz is a double exposure, simultaneously showing Duchamp in pensive profile and smiling into the camera, like twin ghosts passing through each other. An Irving Penn photograph shows him wedged in an unusually narrow corner, like the inside of a parcel waiting to be unpacked. With his gaunt features and slim, long body, he looks like an Edward Gorey illustration.

Henri Cartier-Bresson photographed an older Duchamp (in 1968, the year he died), smoking and staring off with bemused concision past his “Bicycle Wheel,” which occupies the foreground like a Futurist architectural structure. And Duchamp is often explored here through the lens of artist and photographer Man Ray, his frequent collaborator.

Duchamp called into question the role of the artist and the significance of craftsmanship. What is interesting is how his ideas have been both realized and abjured in the 21st century.

Most art being made today foregrounds craft, process, thematic content and cultural engagement — anathema to Duchamp’s vision of art as divorced from the material world. But at the same time, he could not have been more prophetic.

About a year ago, I was researching the Sotheby’s estate sale of actor Robin Williams. If I told you how much someone paid for a mass-produced, generic toy soldier just because Williams owned it, you wouldn’t believe it.

Actually, you would have no problem believing it. Because if a meaningful person once placed their hands on that toy soldier, or that manufactured urinal, it becomes meaningful. For some reason, we all agree on that.

Art is nothing without its cultural context. It is a marvelously self-evident concept, and I guess you could say that Duchamp invented it. Or maybe he just put a name to it. He would almost certainly decline to acknowledge the distinction.

Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection

Through Oct. 15

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Independence Avenue and 7th Street NW

Open daily 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.

Free admission

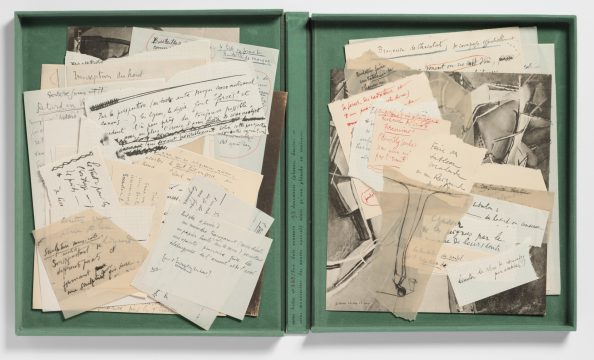

“The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box,” 1934. Marcel Duchamp. Courtesy Hirshhorn.

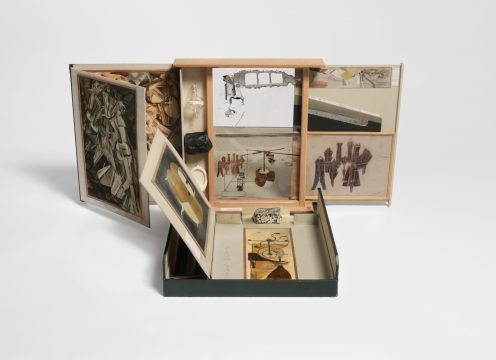

“The Box in a Valise,” 1935-41. Marcel Duchamp. Courtesy Hirshhorn.