Remember Us

By • February 26, 2020 0 1947

GU272 MEMORY PROJECTS — GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY CONFRONTS ITS LEGACY OF SLAVERY

“The affair gave many here a reason for speaking badly about us. No one does this but bad people, as they are dealers of Negroes, who care for nothing except money … the slaves who were under my care conducted themselves well … if they did need to be sold, they could have been sold without scandal and clear danger of losing their souls.”

Dr. Linda Mann interviewing a GU272 descendant. Photo by Claire Vail. Courtesy AA-NEHGS.

So wrote Dutch Jesuit Peter Havermans grimly in October 1838 of the sale of more than 272 enslaved persons from Maryland plantations, owned by the Society of Jesus, due to mounting debts that included small Georgetown College in Washington, D.C. Those 272 — from infants to the elderly — departed on a ship from Alexandria to New Orleans, where they would work sugarcane fields and endure cruel conditions. Lost (almost) to history were the souls that feared for their lives and their Catholic faith.

Georgetown College, circa 1838. Courtesy Georgetown University

AN AWAKENING

In the 21st century, an awakening dawned at Georgetown University, after similar acknowledgments by Brown, Columbia, Harvard and the University of Virginia, that administrators had bought and sold slaves. Georgetown’s slaveholding reckoning would be different, because its sale involved such a large number of people — and because the documentation, both available and to be tracked down, was more than ample.

In 2014, Georgetown student Matthew Quallen wrote an account of the Jesuits’ 1838 sale in the Hoya student newspaper. He urged the university to strip the names of Georgetown Jesuits Thomas Mulledy and William McSherry from buildings named for them because of their involvement in the sale. (It should be noted that university records and history books told of the slavery story.)

In the months that followed, which saw student protests, Georgetown professor Adam Rothman, a member of Georgetown University’s Working Group on Slavery, Memory & Reconciliation, summed up the process then beginning: “It seems to me that the story of Georgetown and slavery is a microcosm of the whole history of slavery.”

The university renamed those two buildings for Isaac Hawkins, the first slave listed in the ship’s manifest, and to Anne Marie Becraft, the founder of a school for black girls in Washington, D.C.

ATONEMENT — AND REPARATIONS?

The university and the Society of Jesus formally apologized for their involvement in slavery and for the sale that shattered families and sold them down the river. It was an emotional day for many when hundreds of descendants gathered for the apology at Gaston Hall and later planted a tree in the Quad, adding soil from Louisiana.

The university announced a legacy designation of admission for descendants of those enslaved and sold, similar to the extra attention given to children of GU alumni, teachers and others. Most recently, an annual fund of $400,000 to support projects and groups in the descendant community was initiated.

In contrast, the Georgetown University Student Association and the GU272 Advocacy Team put together a plan for reparative action. The referendum they proposed called for a fee of $27.20 to be added to each student’s yearly tuition for the benefit of the descendants. Last

spring, students voted to approve the referendum. It was the first proposal of its kind in the United States, displaying support for the continuation of reparations. (Separately, some descendants have called for a $1-billion reparations fund.)

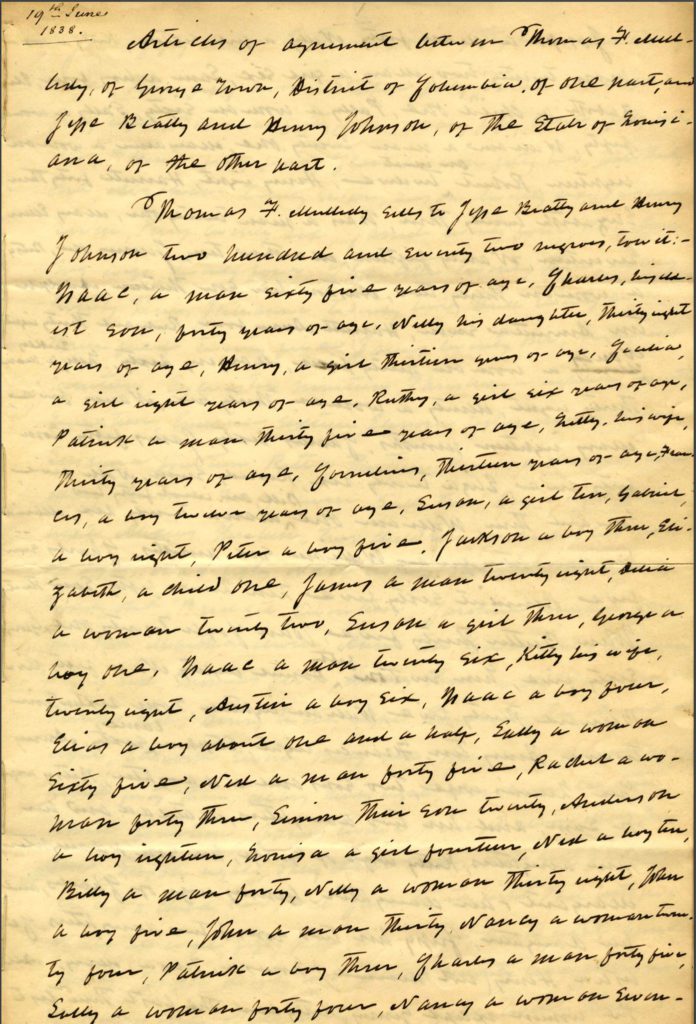

First page of the GU272 Bill of Sale, dated June 19, 1838. Courtesy AA-NEHGS.

Avoiding the word “reparations,” Georgetown University President John J. DeGioia has said: “We embrace the spirit of this student proposal and will work with our Georgetown community to create an initiative that will support community-based projects with Descendant communities … The University will ensure that the initiative has resources commensurate with, or exceeding, the amount that would have been raised annually through the student fee proposed in the Referendum, with opportunities for every member of our community to contribute.”

FINDING THE ANCESTORS

Still, the sorrowful question persists: Who were these good, Catholic people that were betrayed and cast off? And where did their descendants live on and prosper? “What we so often lack is the perspective of enslaved people themselves,” Rothman has noted. As it turns out, Georgetown has an array of genealogical tools to offer those looking to trace connections between past and present.

“A great deal of the credit for discovering the descendants goes to Patricia Bayonne-Johnson, a descendant of Nace and Biby Butler, a husband and wife who were sold

by Thomas Mulledy to Jesse Batey in 1838 and transported to Louisiana,” according to Georgetown University. “Bayonne-Johnson … discovered her connection to Nace and Biby Butler while researching her family tree in 2004. Using documents from the Jesuit Plantation Project, and with help from Louisiana genealogist Judy Riffel, Bayonne-Johnson learned of the story of the 1838 sale and uncovered additional documents, including the manifest of the Katherine Jackson.

“After Georgetown president Jack DeGioia formed the Working Group for Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation at Georgetown University, we created the Georgetown Slavery Archive to replace the defunct Jesuit Plantation Project website and publish additional documents from Georgetown’s archives relating to the university’s relationship to slavery and slaveholding in the Maryland Province, and to the fate of the people who were sold to Henry Johnson and Jesse Batey in 1838.”

Soon enough, Georgetown alumnus Richard Cellini took on the task of researching the GU272 descendant community with his independent Georgetown Memory Project, aided by contributions from fellow alums.

“This is not a disembodied group of people, who are nameless and faceless,” Cellini told the New York Times, which published major stories on the Jesuits’ slave sale four years ago. “These are real people with real names and real descendants.” As of this month, Cellini lists persons identified and located: 227 ancestors; 9,269 direct descendants.

Another website was created last year to assist the search. “The GU272 Memory Project marks the first time that genealogical data about the GU272 will be publicly available. It’s a milestone in online resources for African American family history,” said Claire Vail, director

of creative and digital strategy, American Ancestors & New England Historic Genealogical Society.

Old Sharecropper cabins in Raceland, Louisiana. Photo by Claire Vail. Courtesy AA-NEHGS.

“The GU272 Memory Project was a natural fit for us,” said Vail, who added that they “traveled to Louisiana to capture oral histories from the largest group of descendants. We spoke with at least 30 descendants living in Baton Rouge, Houma and New Orleans, for a total of 50 interviews to date across many families.” Vail commented that finding and digitizing the available documents — “and making it searchable and making it public — is a

vitally important task, both for descendants and for historians. Identifying enslaved people is a vital step in gaining a better understanding of America — past and present.”

Four years ago, Cellini phoned Maxine Crump in Baton Rouge with the revelation that her great-great-grandfather Cornelius Hawkins was one of those slaves sold by the Jesuits to the Louisiana plantation. “Oh my God,” she cried. “Oh my God.” That was Neely, buried in the only Catholic cemetery in the area. “Now they are real to me,” Crump told the Times. “More real every day.”

DESCENDANTS BECOME HOYAS

Among the first descendants to matriculate at Georgetown are Elizabeth Thomas and Shepard Thomas, the children of Sandra Green Thomas, great-great-granddaughter of Sam Harris and Betsy Ware Harris.

“In the mid-1990s, I lived within walking distance of Georgetown. I was pushing my babies around in a stroller, going on campus, without knowing anything about the connection,” Thomas recalled in a Times piece. “I read The New York Times, and I saw the story there. I saw the photo of the cemetery, and I saw Maringouin, La. I went to the website of Georgetown’s slavery archive and saw the names of my relatives … I find it somewhat comforting and amazing that the immediate family remained intact after being sold … When I first read it, I was just looking at the facts. But when you start thinking about it, it is really horrific.”

As if to complete a particular circle of life, Georgetown graduate Elizabeth Thomas is now an ABC News reporter. Last year, she and another descendant student, Melisande Short-Colomb, went to the Jesuit cemetery on the university’s main campus. In front of the tombstone of Thomas Mulledy, S.J., who coordinated the slave sale, they told him: “Look at us now.”

No doubt, there will be more arguments about reparative action by the school and more programs and memorials to follow. Meanwhile, this sinful chapter of Georgetown University and of America is leading to something of a miracle: those once lost to history and are now among us — and remembered.

LEARN MORE:

- slaveryarchive.georgetown.edu/descendants

- georgetownmemoryproject.org

- gu272.americanancestors.org

- gu272.net

Photos of GU272 descendent Donna Comeaux’s family. Photo by Claire Vail. Courtesy AA-NEHGS.