In Defense of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’

By • September 14, 2020 One Comment 3435

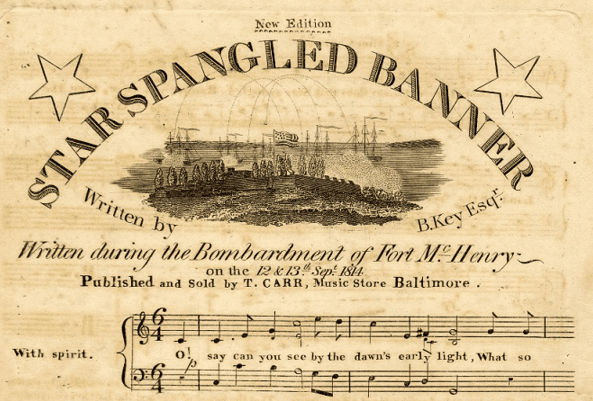

Today, Sept. 14, is the 206th anniversary of the song that would become our national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

While the song and its author, Francis Scott Key — who lived in Georgetown, Washington, D.C. — remain subject to strong criticism, whether by protestors, sports teams or Mayor Muriel Bowser’s working group on renaming D.C. properties, let us appreciate a fuller view of the poem and the writer.

The following is a revised version of a Georgetowner newspaper editorial of Sept. 14, 2016.

“Defence of Fort McHenry,” the original title of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” became a hit after the Battle of Baltimore, when the Royal Navy withdrew away from the harbor in September 1814. The fort took many mortar bombs and cannonballs, but the British could not pass.

Georgetown lawyer Francis Scott Key had sailed earlier with a federal official to meet the top British officers — Admiral George Cockburn and General Robert Ross — on their ship, seeking release of an American prisoner. They had to stay on their truce ship as the enemy launched the attack.

At first an opponent of the War of 1812, Key saw through the morning haze of Sept. 14 that the flag was still waving above Fort McHenry — an incredible, emotional revelation to him — in sight of the conquerors of Napoleon.

This is what is so powerful about the song: it captures how Americans felt about their 38-year-old nation. Its impact cannot be underestimated. For many folks, the hand of God was at work.

Weeks before, on Aug. 24, 1814, the British troops of Ross and Cockburn burned the official buildings of fledgling Washington, D.C., after defeating the Americans at Bladensburg. The Brits entered the nation’s capital unopposed. All of Washington, D.C, Georgetown, D.C., and Alexandria, D.C., were in panic. President James Madison fled to Virginia and then to Maryland. It was a national humiliation we might imagine through the lenses of Sept. 11, 2001.

Some cite the third stanza of “The Star-Spangled Banner” for its use of the word “slave” as proof of racism.

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion,

A home and a country, should leave us no more?

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps’ pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave,

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Key wrote the stanza as an invective against the arrogant British, America’s enemy at the time — from the highest class to the lowest. Yes, runaway American slaves fought with the British, but free blacks and runaway slaves also fought with the Americans’ Chesapeake Bay Flotilla.

A slave owner, Key was conflicted about slavery. As D.C. attorney general, he prosecuted slaves, but also represented them in lawsuits to obtain their freedom — including one against Georgetown College. He was highly respected in the city and in the federal government.

The accusation that the poem itself is racist is off the mark and lacks historical context.

How is Key’s use of the word, “slaves,” who were part of the enemy force, offensive? How many texts contain the word “slaves”? In such excluding minds, what’s next? The sculpture in Francis Scott Key Park on M Street in Georgetown, next to Key Bridge? What about the equestrian statue of liberator Simón Bolívar, a slave owner, at 18th Street and Virginia Avenue, across from the Organization of American States?

We should not let the historiphobes frame such discussion for their narrow goals. Slavery is in the past.

The legacy of that history continues in the form of systemic racism in America. It is something we can do something about in the here and now.

Americans have made amends and have striven to be far better. We are working through the 2020 protests to reach a greater understanding and effect solutions that are equitable for all.

In terms of the history of slavery in the nation’s capital, we can point to Georgetown University, which has sought to atone for its slavery past, as well as to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which opened four years ago, for all Americans, on the National Mall. These accomplishments are unifying and inclusive.

On this day, let us recall that unity we had for a moment 19 years ago this month during our shock and recovery from the destruction and loss of life in New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia and take to heart, renewed, the fourth stanza of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

O! thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand,

Between their loved home, and the war’s desolation.

Blest with vict’ry and peace, may the Heav’n rescued land,

Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation!

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto: “In God is our Trust”;

And the star-spangled Banner in triumph shall wave

O’er the Land of the Free, and the Home of the Brave.

Glad to read a article from someone who wants to do something more then cause mire racism.

All colors have had ugly pasted.

If you read history, most war like nations, Europe, Africa, Mexico etc attacked weak countries and villages and made those people their slaves.