An Exhibit of Her Own: Whistler’s “Woman in White”

By • July 28, 2022 0 2192

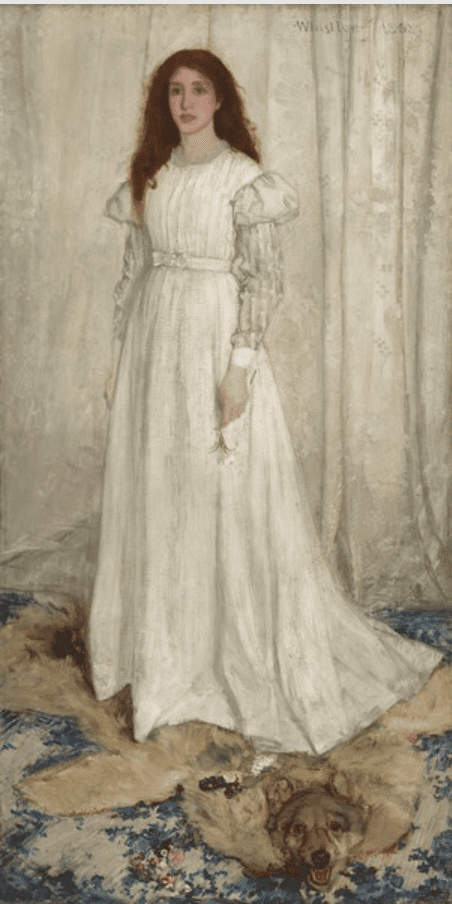

One of the treasures of The National Gallery of Art’s permanent collection, James McNeill Whistler’s “Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl” looms large in an exhibit of her own: The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler (on exhibit through October 10, 2022).

Acquired by the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in 1943, the masterpiece painted in London in the winter of 1861-1862 by the American painter Whistler stands apart from other portraits of “women in white” with which she has shared gallery space in the permanent collection.

A stark comparison is found in John Singer Sargent’s 1883 portrait “Margaret Stuyvesant Rutherfurd White (Mrs. Henry White).” From a prominent American family and married to an American diplomat, the wealthy Daisy White arranged a commission for her portrait in which she wears an elaborate stylish crinolined gown adorned with lace, satin and tulle, her hair styled, her hand holding a fan and opera glasses.

In contrast, in her portrait, Hiffernan, an unknown model, wears a white cambric housedress covering her body from neck to toe and merging with the white curtain behind her. Her red hair hangs long and loose, as she stands on a fur rug, with a simple flower falling from her hand by her side.

In this exquisite exhibit centering on Hiffernan, her life-size portrait is accompanied by “Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl,” (1864), where she stands against a mantelpiece, her face reflected in a mirror, gazing at what is possibly a wedding ring on her finger. In “Symphony in White, No. 3” (1865–1867) she poses in a horizontal position lounging on a white couch with another model.

What we do know, apart from Whistler’s paintings, is that Hiffernan was an intelligent young Irish woman from a poor immigrant family.

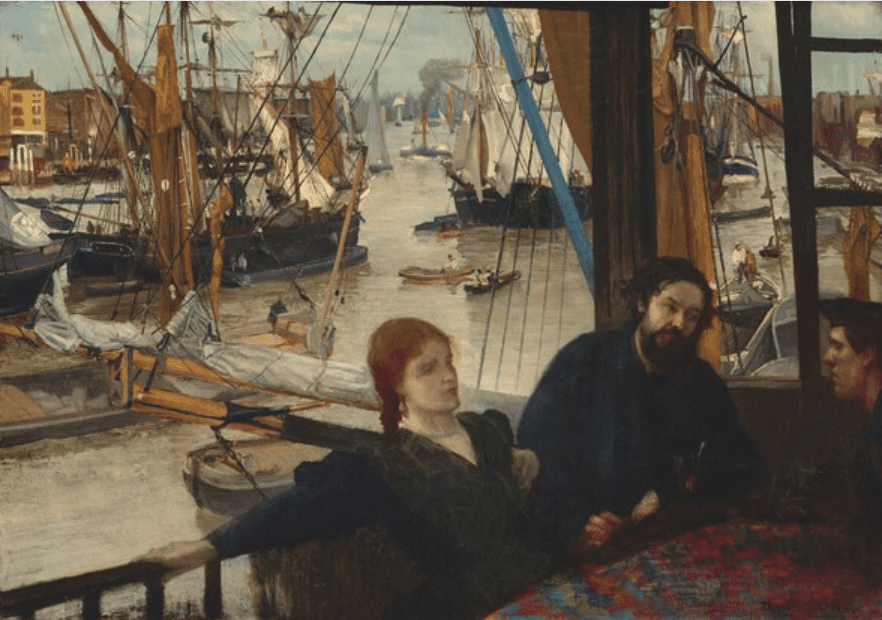

There are clues as to how Whistler first met her in an early work, “Wapping” (1860–1864). Dressed in a low-cut black top, she sits, with two man at a table in Angel Inn, a working-class pub in London’s East End, set against a background of ships, sails, rigging, booms, and masts on the Thames river.

Whistler’s “Whapping” 1860-1864. Courtesy NGA.

“Purple and Rose: The Lange Leizen of the Six Marks” (1864) presents her dressed in a kimono amid Whistler’s Asian art collection. Some have questioned whether she’s a model or only another decorative exotic object.

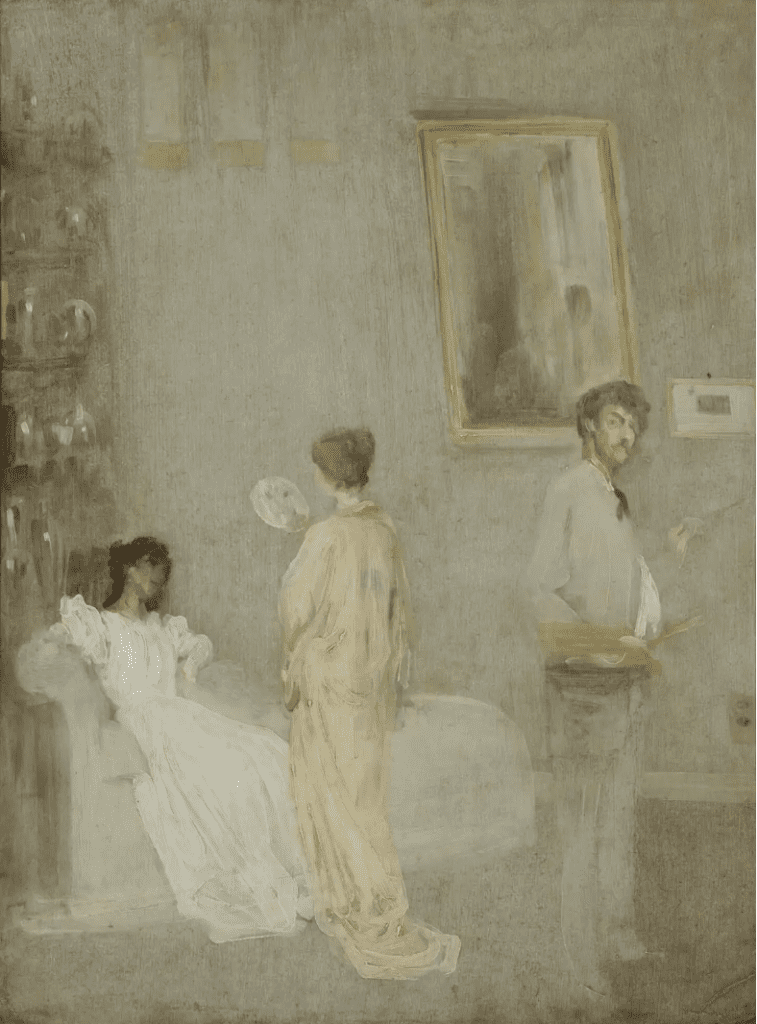

“The Artist in His Studio” (Whistler in His Studio) (1865/1872, 1895) is an oil-on-paper mounted on wood, the only one with them together. While she sits on a sofa in the back of the studio, he stands facing the viewer with his back to her. A third figure between them seemingly separates their realms, where he’s the artist, she his muse. While she seems to be in plain sight, there’s more to the mystery of this woman who’s at once Whistler’s mistress, model and inspiration.

Whistler’s “The Artist in his Studio,” 1865-1866. Art Institute of Chicago.

In the second gallery are prints, letters and stories including details of Whistler’s other affairs — all offering information of their life together. Sadly, there are no photographs of Hiffernan. The only other artist known to have painted Hiffernan is Gustave Courbet whose paintings, like “Jo, la belle Irlandaise” (1865–1866), present another view.

The final gallery offers other paintings of women in white. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s “Ecce Ancilla Domini! (The Annunciation),” 1849–1850, oil on canvas is the only work prior to Whistler’s. It is suggested that the symbols of the Annunciation inspired Whistler’s work, while the other paintings presented were influenced by Whistler.

Two works suggest spooky stories — John Everett Millais, “A Somnambulist” (1871) and Frederick Walker, “The Woman in White” (1871) — and so bring to mind another work with this familiar title.

Many know of Whistler’s painting, not from any museum visit, but from seeing it on the cover of Wilkie Collins’s sensation “The Woman in White.” Published around the same time in London, the novel centered on a mysterious woman dressed in white. There is no connection, a point that Whistler would state in “The Athenaeum.” Not only did he never intend to illustrate the novel, he had not even read it!

Whistler reaffirmed that his painting is simply “a girl dressed in white standing in front of a white curtain” and that his painting was related to music and poetry, intended to create a mood rather than literature narrating a Victorian story book.

Whistler’s “Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl,” 1861-1862. Courtesy NGA.

Collins’s “The Woman in White,”brings up another difference. While the story ends with an answer to who was the mystery woman and what she was about, “The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler,” now at The National Gallery of Art until Oct. 10, 2022, is just the beginning of questions about who was she — Whistler’s Woman in White.

For more information on this exhibit go here.