Last Chance: Matisse and Modigliani in Philadelphia

By • January 12, 2023 0 3373

Sunday, Jan. 29, is the last day to see “Matisse in the 1930s” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and “Modigliani Up Close,” a few blocks away at the Barnes Foundation.

Last year was the centennial of Albert Barnes’s absurdly rich trove of Impressionist, Post-Impressionist and modernist paintings, hung with art and artifacts from other time periods and cultures, and the 10th anniversary of its controversial relocation to Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway from leafy Merion on the Main Line.

The founder’s dense wall ensembles were painstakingly recreated in the new building, designed by Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, as was the set of three arches for which Matisse painted “The Dance,” a 45-by-15-foot mural Barnes commissioned in 1930.

That commission was an inflection point for Matisse, who turned 60 at the end of 1929. Having spent the prior dozen years in sun-drenched Nice painting interior scenes, he began to formulate compositions of flattened shapes and strong colors, without abandoning representation entirely. The large-scale “cut-out” technique — his primary medium after a 1941 operation for abdominal cancer confined him to bed and a wheelchair — began on a small scale as a design tool for the Barnes mural.

“Matisse in the 1930s” is therefore ideally paired with a Barnes visit, to see the mural and many more Matisses, including such well-known paintings as “The Joy of Life” of 1906; “The Red Madras Headdress,” a portrait of Matisse’s wife Amélie, of 1907; and “The Music Lesson” of 1917. There is also a special exhibition on the lower level of archival photos and correspondence titled “Matisse, Dr. Barnes, and ‘The Dance.’”

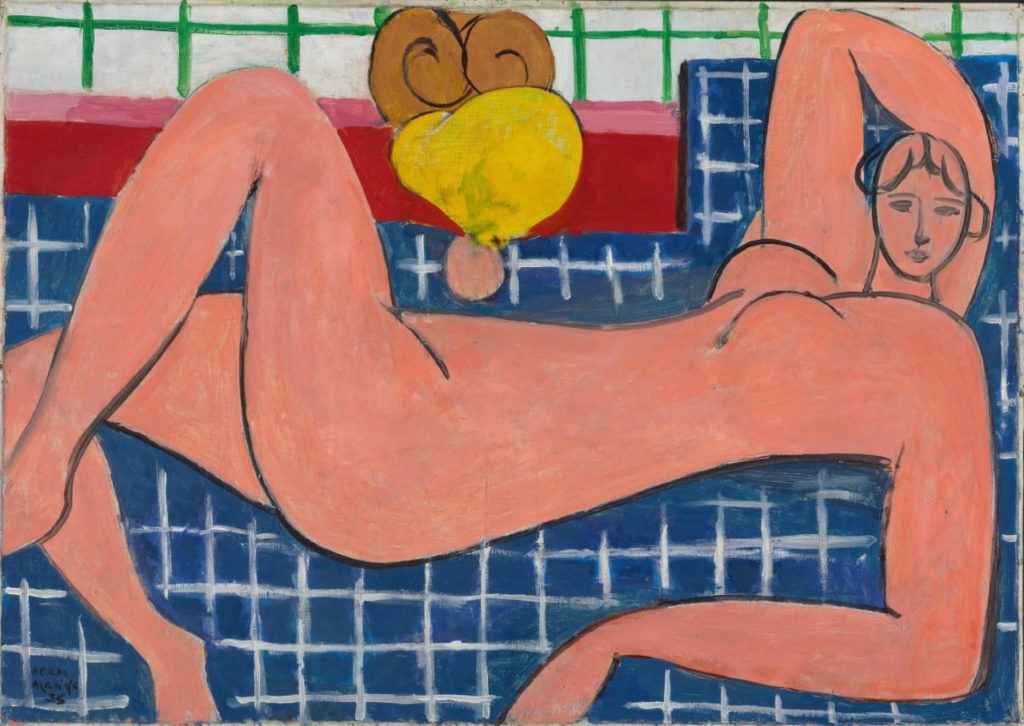

But one could easily spend several hours just in “Matisse in the 1930s,” organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art with the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris and the Musée Matisse in Nice, which provided key loans, as did the Baltimore Museum of Art — notably “The Yellow Dress” of 1929-31 and “Large Reclining Nude” of 1935 — and other museums.

Unfortunately, an adversarial atmosphere clouded the launch. After unionized staff went on strike several weeks before the exhibition’s scheduled Oct. 20 opening, the museum brought in outside art handlers to install it. Agreement was finally reached on a new contract and union members returned on Oct. 17.

The expansive show features works in a variety of media, not only paintings and sculptures but line drawings, book illustrations, two large tapestry cartoons and a 10-foot-tall mantelpiece painted with four female figures, “Le Chant” of 1938, commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller. “Woman in Blue” of 1937, for which Matisse’s frequent model, longtime assistant and later caregiver Lydia Delectorskaya posed, is on view next to the blue skirt Delectorskaya fabricated at Matisse’s request and wore (the blue bodice is missing).

Another highlight is a 10-minute video of a 1939 performance by the Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo of “Rouge et noir,” choreographed by Léonide Massine to music by Dmitri Shostakovich, for which Matisse designed the set and costumes.

The other film footage shows Matisse outlining what would become the Barnes mural with a crayon or charcoal stick at the end of a pole; he and, charmingly, his little dog go up and down the rolling staircase that gives access to the upper section. Nearby are studies for the mural and a full-size sketch from the Nice museum of the central figure, one of eight highly simplified nude female figures inspired by French folk dancers.

The term “odalisque” — a Western depiction of a harem scene — is unavoidable when discussing Matisse. Earlier French master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres is as famous for paintings such as “La Grande Odalisque” of 1814, “Odalisque with Slave” of 1839 and “The Turkish Bath” of 1863 as for his portraits of the circle of Napoleon.

Following Ingres’s lead, academic painters took up the odalisque with gusto. The genre had the advantages of extending the tradition of the female nude (formerly a goddess, a nymph, a woman ravaged by a god, Eve, etc.), drawing on pro-Greek/anti-Turk sentiment, adding the spice of the Orient and explicitly playing to the male gaze during a period when public sexual expression was associated with vice. (What made Édouard Manet’s “Luncheon on the Grass” and “Olympia” of the 1860s so shocking was that they depicted a naked Frenchwoman, presumably a prostitute. Naked enslaved Turkish concubines, on the other hand, were fine.)

Though Matisse had painted and sculpted many female nudes, they tended to be generic and stylized, often symbolic, as in the Barnes mural. By the time of the cut-outs, he was a virtuoso manipulator of the curves of women’s bodies, compositional elements in works of suggestive, but rarely erotic, beauty. As for Matisse’s many odalisques of the 1920s and ’30s, one might call them meta-odalisques. Posed in makeshift “Oriental” settings, his models are clothed in and surrounded by decorative textiles that receive as much attention from the artist as the women’s faces and bodies; the harmony of the whole was his goal.

What was Amedeo Modigliani’s goal in painting more than two dozen of what the Washington Post’s Sebastian Smee called “the sexiest [female nudes] in modern art”? Five of these magnificent landscapes of the female body, from the Met, the Guggenheim, MoMa, Oberlin and Lille, are on view in “Modigliani Up Close.” I think if you had asked Modigliani this question, he would have said (in Italian-accented French): “I like to paint them, people like to look at them, and if the prudes are horrified all the better.”

Installation view of the “Modigliani Up Close” exhibition at the Barnes Foundation. Photo by Richard Selden.

In an adjacent space, one encounters a more sensitively painted female nude, “Standing Nude (Elvira),” c. 1918, holding a sheet over her pubic area, and a portrait of the same dark-haired model, clothed, her left hand holding her cheek, “Elvira Resting at a Table,” c. 1918-19. Nothing is known of Elvira, but she appears to be in her early teens (which raises another issue).

“Elvira Resting at a Table, c. 1918-19. Amedeo Modigliani.

A handsome and gifted Italian-born Jew who lived a brief, semi-scandalous life, Modigliani is an elusive figure and, to many, a fascinating one. His idiosyncratic portraits — their subjects stylized with elongated necks and (usually) blank, almond-shaped eyes; their settings minimal and claustrophobic; the painter’s little wormy signature in a corner — are the work of a modern mannerist or perhaps a mannered modernist.

That there is rampant forgery of Modiglianis adds to the intrigue that surrounds him and his work. The label text and enlarged infrared images and X-radiographs of several of the 39 paintings in the Barnes exhibition address both the authenticity question and Modigliani’s working methods, commenting on overpainting and on canvas sizes (he often used horizontal “marine” canvases in a vertical position), sources and threadcounts.

Along with early paintings, the first of the exhibition’s five galleries displays a circle of eight narrow limestone heads from around 1912, carved in the mode, inspired by African and Cycladic sculpture, of Modigliani’s Paris neighbor Constantin Brancusi.

The Barnes owns 12 Modigliani paintings, the most in one place, though they are not hung together. The National Gallery of Art owns an equal number, all the gift of Chester Dale, stunningly installed in a single East Building room.

Offering a similar experience, the last gallery in “Modigliani Up Close” (to the right as you enter) contains seven portraits, including three of Jeanne Hébuterne, who lived with Modigliani from 1917 until his death, from tubercular meningitis, and hers, by suicide the following day, in 1920.

In that gallery, “Young Woman in a Yellow Dress (Renée Modot)” of 1918 is a standout, unusual in that her eyes have eyeballs and behind her is a wall hanging in an abstract pattern of white, gray and black. Its distinctive elements, notes the label, “may be indebted to the work of Henri Matisse.”