Featured

I Scream, You Scream, We All Scream for Georgetown Ice Cream Shops!

Featured

Weekend Roundup: July 25-28

Food & Wine

42nd Annual RAMMYS Fetes Local Restaurants, Bars

News & Politics

MPD Provides Rapid Response to Spike in Georgetown Crime

Featured

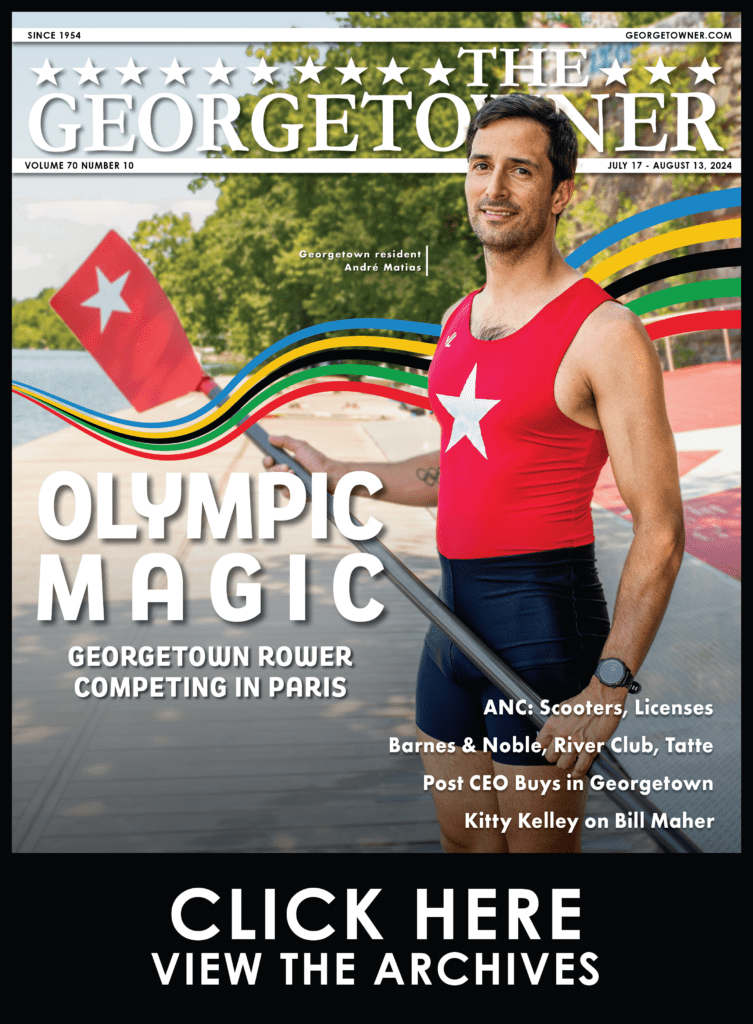

Georgetown Rower to Compete at Paris Olympics

35th Rammys: Colorful, Tasty Salute to D.C. Restaurants

• July 31, 2017

Winners included Tarver King, Jemil Gadea, John Grace, Ryan Ratino, DC Brau Brewing, Pearl Dive Oyster Palace, Cava Group and Hazel.

‘The Kitty Kelley Files’ Premieres July 29

• July 27, 2017

Kelley’s celebrity profiles will make their TV debut this Saturday on the Reelz network, starting with actress Drew Barrymore.

Hyde-Addison School Construction Project Begins

• July 24, 2017

On July 20, representatives of all the major stakeholders met to go over neighbors’ concerns.

A Loss in the Family: Jim Vance

•

The longest serving broadcaster in the D.C. area succumbed to cancer last Saturday.

GBA Touts Georgetown Main Street Proposal

• July 20, 2017

Attendees at the Georgetown Business Association’s July 19 networking reception rallied around the neighborhood’s pitch for a Main Street program.

RISING TIDES How the Wharf Is Set to Redefine D.C.

• July 12, 2017

Phase 1 of the Wharf, the multibillion-dollar project springing up from the Southwest waterfront, is set to open Oct. 12. PN Hoffman’s Monty Hoffman couldn’t be more excited for Washingtonians […]

Les Grandes Vacances

• July 9, 2017

Suiting Up For Summer Sun A classic French-inspired home is always in style for a good old swimwear shoot. It’s officially our prime tanning spot, Victoria approved. Go for a […]

$25,000 Reward for Tips on Water St. Shootings

•

The perpetrators of the fatal shooting of a 19-year-old from Severn, Maryland, and the shooting of another unidentified man around 3 a.m. Saturday morning, July 8, on Water Street in […]

First Whacks at Wawa — and More ANC Highlights

• July 3, 2017

Meeting Thursday, June 29, before its summer break, the Georgetown-Burleith Advisory Neighborhood Commission tackled some hot-button town topics: DC Streetcar, the District Department of Transportation’s plans for protected bicycle lanes […]

Get Away to the 18th Century in Williamsburg

• June 21, 2017

Georgetowners are fortunate to live in a neighborhood steeped in the nation’s heritage. Some colonial and Revolutionary sites are right around the corner; others are short drives or train rides […]