Does Bob Woodward Ever Get Angry?

By • October 13, 2020 0 3236

Why is Bob Woodward’s new book called “Rage”?

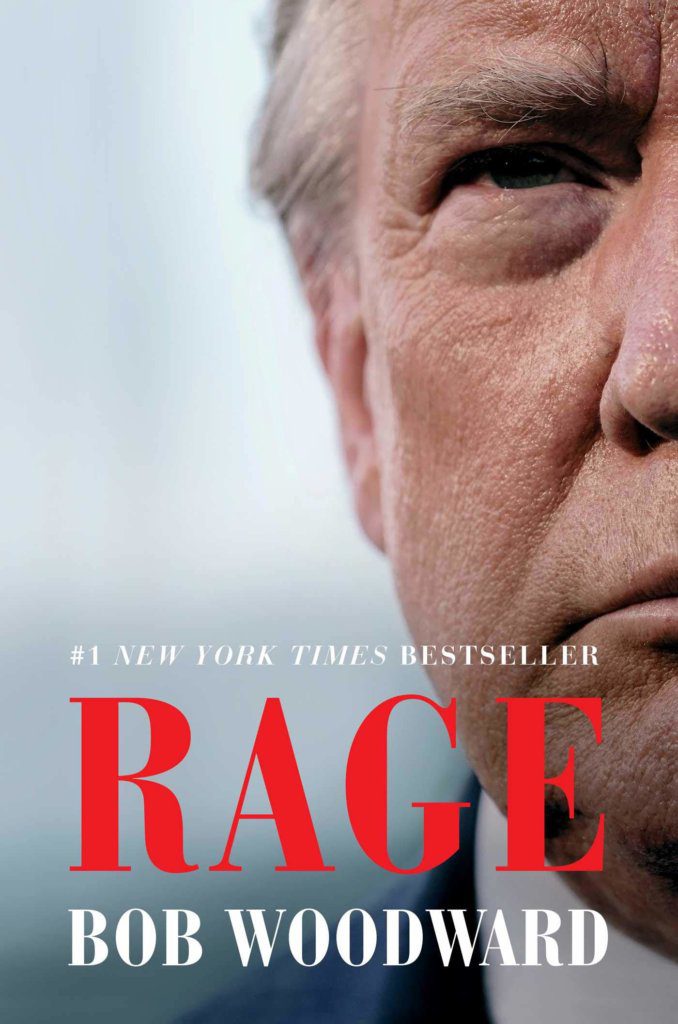

The half of President Donald Trump’s face on the book jacket doesn’t look particularly angry. And in the excerpts from Woodward’s 17 one-on-one interviews with the president, there is not a spark of Trumpian fury.

No, we have met the enraged and it is us. Millions are furious at the way Trump has led the country and a roughly similar number, equally upset about societal trends, are furious not at Trump but at the first group.

The title of Woodward’s latest addition to the shelf of books he has written about nine consecutive presidents refers to candidate Trump’s comment to Woodward and Robert Costa: “I bring rage out.” Trump later attributed it to his opponents’ jealousy of his accomplishments.

But clearly much of the provocation is intentional, as in “owning the libs,” and Trump Derangement Syndrome — echoing Charles Krauthammer’s coining of Bush Derangement Syndrome during Dubya’s White House years — is real.

The one person who isn’t enraged? Midwesterner, Yalie, naval officer, journalist’s journalist and longtime Georgetowner Bob Woodward, who seems to have a natural immunity.

There was that one scene in the film “All the President’s Men” when Robert Redford, as Woodward, blurted out to Deep Throat: “Listen, I’m tired of your chickenshit games!” (Whether these were Woodward’s or screenwriter William Goldman’s words, I don’t know.)

And in Chapter 38 of “Rage,” the interviewer appears to lose his patience: “He was blowing off both me and the list [of “14 critical areas” relating to the pandemic “where my sources said major action was needed”]. Elsa, my wife, was in the room during the call. At times I raised my voice in order to be able to complete a question or press the president to answer. At one point, she told me to stop yelling.”

Few of us would have lasted as long as Woodward without saying, as Joe Biden did in the first debate, “Will you shut up, man?”

But temperament and stamina have been Woodward’s journalistic and authorial superpowers since the Pulitzer Prize-winning reporting he and Carl Bernstein did starting in 1972, recounted in their two masterpieces: “All the President’s Men” and “The Final Days.”

Woodward’s first book on Trump, “Fear: Trump in the White House” of 2018, was written without access to the president. “I’m used to that,” Woodward says. “Rage,” however, was written with seemingly unlimited access: “For 10 months, I was able to call him.” And Trump got in the habit of ringing up Woodward on Q Street without warning.

Is there an optimal amount of access? “The more, the better,” says Woodward.

Apart from Trump’s constant chaotic reiteration of his worldview (some would say alternative reality), events made organizing this book a challenge. “It was a national security book” at first, Woodward says, “and then the virus hit.” Having to “in a sense write a second book,” and do so remotely, it became “very much a telephone exercise.”

This had its advantages, however, in getting subjects to talk. “The phone and the tape recorder tend to disappear,” he says. Of course, a reporter’s success or failure at getting past a source’s inhibitions, defenses and spin was more of an issue with other figures quoted in “Rage” than with the president himself. “Trump is different. He pretty much says what’s on his mind,” says Woodward (this wasn’t news). “I let him have his say.”

The sections based on interviews with participants in and witnesses to events covered in “Rage,” the majority on deep background, are both convincingly written and highly readable. We gain insight into figures like Dan Coats, Lindsay Graham, James Mattis, Rod Rosenstein and Rex Tillerson, not only from the narrative but from the way they (presumably) told Woodward their side of the story.

“Rage” offers new information about the White House’s interaction with China and North Korea, the Mueller investigation and — triggering criticism of Woodward’s supposed holding back of “what he knew and when he knew it” — the pandemic.

In the epilogue, Woodward refers to the “shadowy presence of Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner,” who he calls “[h]ighly competent but often shockingly misguided in his assessments,” yet it is Kushner who, earlier in the book, gives the clearest explanation of how Trump operates. And although the last line of “Rage” is “Trump is the wrong man for the job,” Woodward bends over backward to be fair (he credits assistant Evelyn M. Duffy for insisting on fair treatment for all), correcting statements and expressing skepticism with a light touch.

What’s more, when statements are accurate, or relatively so, this is underlined in the text. Near the end of the footnotes, one even finds this: “Trump has some real accomplishments that are not understood. The NAFTA replacement, called the USMCA, fully is a success” and “Trump has a compelling case that the trade deficit of some $500 billion with China is a ripoff.”

For some time now, Woodward has been writing what might be called journalism for the long haul. “You keep trying to learn about the presidency,” he says. Governance and politics are “sometimes at war with each other” and “sometimes they can work in tandem” — for good or otherwise, as he knows firsthand and has been instructing us, calmly, for nearly 50 years.