Portrait of a Visionary: Maya Lin

By • September 14, 2022 One Comment 2993

There aren’t many artists in the last 50 years who will have more impact on the world than Maya Lin. I’m not talking about the “art world” — that ill-defined stratosphere increasingly controlled by jacked up billionaires and their dealers — but the real, lived-in world of regular people. People who go on hikes, who visit crowded cultural landmarks on vacation, who have children, who have lost loved ones, who are concerned about the future and who carry hope with them anyway.

That may seem hyperbolic, but I’m willing to bet time will bear me out.

Opening on Sept. 30 at the National Portrait Gallery, “One Life: Maya Lin” is an intimate exhibition tracing Lin’s life from childhood to the present. In consultation with the artist herself, this latest edition of the museum’s “One Life” series will bring together an assortment of Lin’s sculptures, sketchbooks and creative material, as well as family photographs and personal ephemera, to offer insight into Lin’s artistic process and remarkable career.

“This is not a retrospective,” says exhibition curator Dorothy Moss. “It doesn’t represent the breadth of her work. But we hope that audiences will walk away with an understanding of how this influential artist, architect and environmental activist approaches her work, what shaped her vision as a young person and how she’s been able to hold onto that vision throughout her career.”

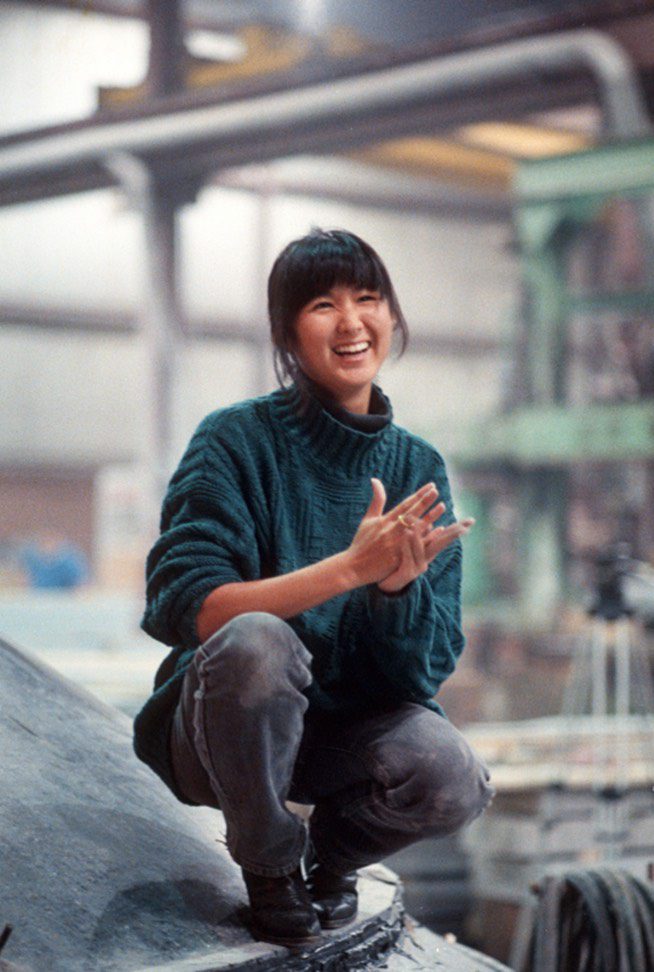

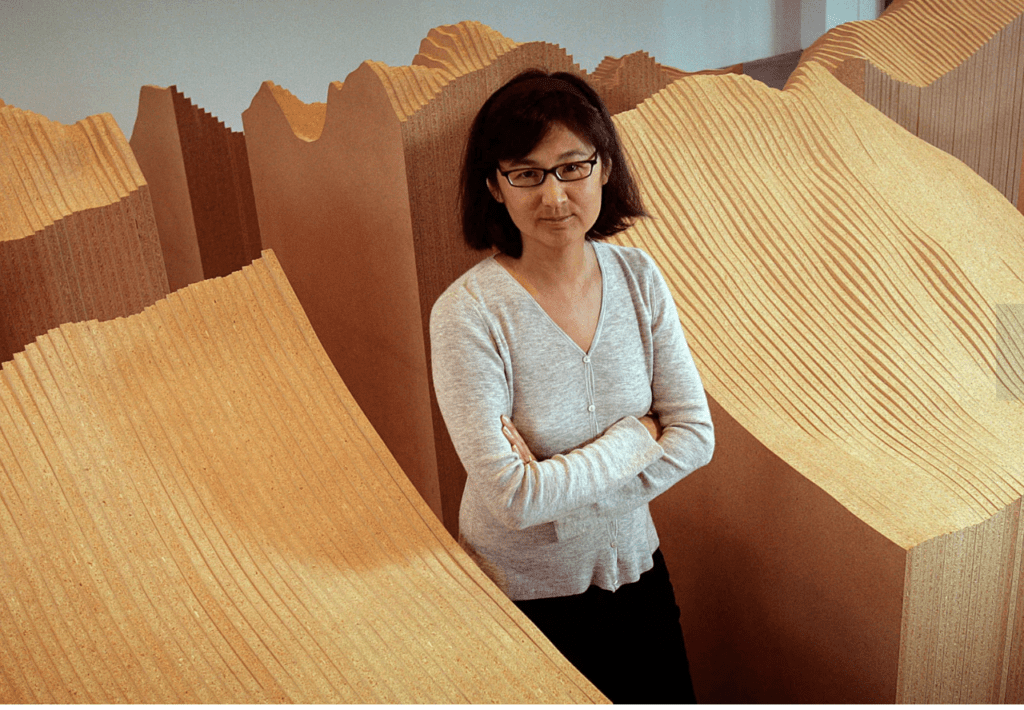

Maya Lin with her sculpture Blue Lake Pass (2006). Britannica.

Lin was hurled into the public eye in 1981 when her design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was selected through a nationwide competition and became a subject of national controversy. The design was an unadorned wall of black stone, sunken below ground level in a V-shaped trench. There were no pictures, no sculptures, nothing physically representative of the war itself. Just the names, etched in the stone, of the 58,318 servicemen and women who lost their lives during the war.

Objectors called it “a black gash of shame and sorrow,” “a nihilistic slab of stone.” At one point the project’s building permit was delayed due to the political opposition. Issues were ultimately worked out — in part by the addition of a bronze sculpture by Frederick Hart featuring three young soldiers (which, as far as these things go, is not bad) — and Lin’s design was left more or less intact.

Section of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, designed by Maya Lin, dedicated 1982; in Washington, D.C. Photo by Sherry Talbot, iStock/Thinkstock. Britannica.

At the time this was all happening, Lin was a 20-year-old undergraduate studying architecture at Yale. She is also of Asian descent, which drew obscene amounts of attention to the issue, even if it was rarely referenced directly. (Lin is Chinese, not Vietnamese, but as Korean American choreographer Dana Tai Soon Burgess says, “People don’t often understand the diversity and complexity of our Asian American community — especially back then.”)

The exhibition includes two articles — one from Newsweek, one from The Washington Post — that make clear how Lin’s heritage and gender was a major factor in her treatment and interpretation by the press. “Her identity as a Chinese American woman was inseparable from the memorial’s design to many people,” says Moss. The show even features a wide-brimmed hat that Lin used to cover her face from the press during the memorial’s unveiling.

Today, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall is the most visited war memorial in Washington — and in many ways the most beloved. While some of that is the straightforward stuff of how many people touched by that war are still around today to visit the memorial (and to drag their families along with them), a lot of it also has to do with the quiet power and starkly overwhelming beauty of the memorial experience in itself.

Portrait of Maya Ying Lin who designed the Vietnam Memorial. Washington D.C. Photo by James P. Blair/National Geographic/Getty Images.

Lin’s design intuitively forecast the evolving postwar sentiment, and the resulting final construction transformed the idea of a memorial for a postmodern world — one that doesn’t browbeat visitors with overbearing patriotic vanity. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial is the anti-Arc de Triomphe, and the world is better off for it. War is not glory, Lin’s wall suggests. War is people and land. War does not happen in a vaulted arena 20 feet above our heads. War happens on the ground, to our bodies. War is not a fable — war is us.

The wall also became the standard-bearer for all memorials since, from countless World War II memorials throughout Europe erected in the 1980s and ’90s (Google Sol LeWitt’s 1987 “Black Form – Dedicated to the Missing Jews”) to the in-development Gulf War Veterans Memorial, the design of which will serve as a kind of conversation piece to the Vietnam memorial.

Looking at the arc of Lin’s work, it is remarkable how frequently she seems to zero in on these deep (and deeply accurate) foresights into major issues of our day. Her interests and concerns as an artist have a way of mirroring the broader social, environmental and, in many cases, political currents of our time.

Perhaps her longest and most enduring fixation, both professional and personal, is the environment. “Everything Lin does is tied to a deep connection and understanding of the natural world,” says Moss. “She grew up in rural Ohio amidst forests and rolling hills, a wealth of wildlife just outside her house. She was an introverted child who loved the outdoors and forged a deep connection to the natural world. Her commitment to the environment comes from that place.”

Lin’s diverse portfolio includes immersive earthwork installations (her series of “Wave Fields,” as well as “Eleven Minute Line”) and architectural projects that echo their surrounding environments (the Riggio-Lynch Chapel in Clinton, Tennessee).

It is because of this elegant blend of art, architecture and landscape that she was recently commissioned to create an installation for the campus of the Obama Presidential Center in Chicago. Titled “Seeing Through the Universe,” the sculpture will feature an upright “oculus” piece that mists and a flat “pebble” piece that fills with water, which then cascades over.

As Lin’s career progressed, so did the alarm around climate change and the need for environmental activism. She quite naturally directed her work towards it. Last year, she created one of the most powerful art installations ever to address climate change. “Ghost Forest” was a towering stand of 49 dead cedar trees in Manhattan’s Madison Square Park, erected to raise awareness of ecosystem die-off.

Maya Lin’s Ghost Forest, brings a towering stand of forty-nine Atlantic white cedar trees, victims of salt water inundation due to climate change to downtown manhattan’s Madison Square Park. Courtesy Mayalinstudio.com.

From war to global warming, Lin seems to have made a career out of trying to make sense of one heartbreaking man-made catastrophe after another. “There is this deep caring for the earth in her work, but also a sense that the earth is fleeting and that it’s under attack,” says Dana Tai Soon Burgess, choreographer-in-residence at the National Portrait Gallery. “So, she creates these pieces which are thoughtful, aesthetically sublime, understated, but they’re sort of permeated with a sense of sadness and mourning.”

“Her work has been environmental for a long time,” he says, “but it’s evolved to become much more specific to environmental preservation.”

In response to the “One Life” exhibition, on Oct. 16, 23 and 30, Burgess will debut a new work at the Portrait Gallery titled “Surroundings: A Tribute to Maya Lin.” Burgess will also be on hand prior to the 6 p.m. performances to sign books (his memoir, “Chino and the Dance of the Butterfly,” was just released by University of New Mexico Press).

The 25-minute dance piece features eight dancers, a cellist, a pianist and two opera singers, with the suite of music chosen to reflect images about the environment and mourning. “I didn’t want to do a linear piece,” says Burgess. “Maya wouldn’t have been interested in that either. I became much more interested in the way she was looking at the concept of the death of the environment. So, the work is more about looking at her creative process and about what happens in the inner emotional landscape of an artist like Maya. I’ve come to think of it as a series of memory pictures, tableaus, images of how she tries to harness her environment. They are poetic and abstract, much like her own work.”

“Mourning and loss is very much a part of Lin’s work,” Moss agrees, “but renewal and resilience is also a key message for her. And whether she’s talking about the Vietnam Veterans Memorial or her work on the environment today — like the ‘What is Missing’ project — she is offering us information to process the current moment, and she’s helping us think about what can be done and what can be restored. She’s very much committed to providing her audience with tools and information to make a change, to create a new course of action.”

Perhaps her most ambitious project, “What is Missing?” is described by Lin as a memorial focused on the environment, highlighting species and places that have gone extinct or will most likely disappear if we do not act to protect them. The multifaceted project takes the form of permanent sculptures and temporary media exhibits, as well as a robust online presence at whatismissing.org. Through this project, Lin wants to present us with new ways to see different outcomes for our planet and for ourselves. In the meantime, “One Life: Maya Lin” will surely offer audiences a new way of understanding the artist herself.

- “One Life: Maya Lin,” Sept. 30, 2022 – April 16, 2023

- “Surroundings: A Tribute to Maya Lin,” Oct. 16, 23 and 30, 2022

National Portrait Gallery, 8th and G Streets NW. For more information go to npg.si.edu.

So excited for Burgess’ next dance!